A reflection on “The Networked Student”, “Rethinking Learning: The 21st Century Learner“, “Connected Learning: An Agenda for Research and Design“, “The Global One-Room Schoolhouse“, and “Becoming a Networked Learner” (Mancabelli & Richardson, 2001)

Education is a profoundly political tool. I’m hardly blowing any minds with that argument, I know.

Still, with this week’s readings, I found a broadening of my perspective, so far focused on the mind and its knowledge-building systems, to a more holistic consideration of learners as embodied and meaningfully situated in diverse socio-cultural contexts.

In reading “Connected Learning”, I was struck by the urgency of the emphasis the researchers placed on linking educational reform with an equity agenda. Their point is powerful — if we push for a more socially-embedded system of education that recognizes, speaks to, and is shaped by students as “whole people”, we cannot ignore the contexts they come from and are headed into.

If instead we fail to focus on equity and collective outcomes, our work as educators can and will only serve to strengthen long-standing systematic advantages of privileged learners. I believe that education should serve as one tool — a fundamental tool — for rising the tide that “lifts all boats”. The question, then, is how we can design connected learning environments that are inclusive and democratic in their reach and in their results.

I argue that equitable, networked, and interest-driven learning requires a redistribution of three often scarce resources: support, space, and time.

Support: The Fallacy of the Digital Native

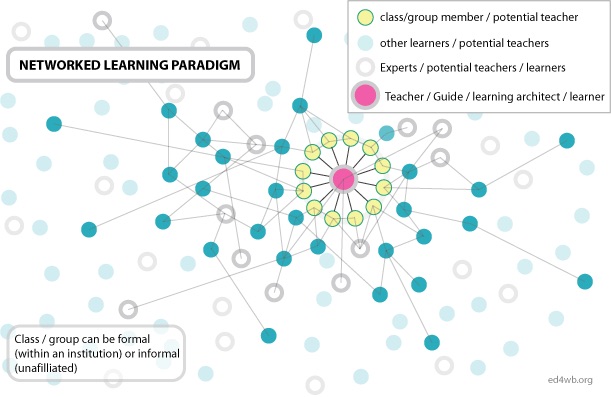

Connected learning principles require an upheaval of the hierarchical status quo in schools, in which power and valued participation rest in the teacher and in high-performing students. Last week, I explored the inadequacy of social hierarchy in representing contemporary connected systems, using instead the imagery of networked nodes and links.

Networked Learning Paradigm, Copryight Ed4wb.org

In “Part 1: Challenges” of the Connected Learning text, the authors note that what, in some instances, appears to be “an opposition to academic achievement among African American and Latino students” is instead a resistance to systemic practices that “devalue their linguistic practices, distinct learning styles, and modes of self-presentation . . .”

It’s clear that many of our most vulnerable learners have been failed by the status quo.

The health of transformative learning networks depends on making explicit the rule that “everyone can participate.” We should look to design learning experiences that actively invite participation and allow for diverse ways in which learners can contribute, including those who have more rudimentary mastery of content or non-normative modes of self-presentation. The teacher’s role here is to be a “Network Architect”, setting the foundation for a system that respects all individuals.

In both “21st Century Learning” and “Becoming a Networked Learner” we saw a rejection of the banal proclamation that today’s young people are “digital natives”. Class status far too often often determines if learners’ have access to the Internet and learning supports at home or otherwise out-of-school. Even for those students who do have regular access to and engagement with the online world, we should not assume that they innately know best practices for building sustained, passion-based, self-directed learning using those resources. Instead, learners need the modeling and coaching of supportive mentors who practice networked learning themselves.

And so a rallying call for teachers to resume their roles as learners by engaging in, reflecting on, and assessing their own experiences in connected learning. “Becoming a Networked Learner” gives us a handy step-by-step guide to building our Personal Learning Networks and reminds us of a crucial point: “what we learn about how to interact with others online is just as important as what we learn about the topic at hand.” Moving from an expert to mentor status asks that we remember that how we interact with our learners is often more important than the subject matter content we are sharing. Knowing first-hand the thrill and terror that come in moving from an observational to participatory mode in a networked community can give educators empathy when guiding their learners to make the same move.

Support of students as “whole people” who have value regardless of their level of mastery is key.

Space and Time: Homo Ludens and the Third Space

Homo Ludens (the Playing Man) has two basic needs: space and time. Entering into the flow of playful tinkering — creating, observing, and tweaking in an ongoing trial-and-error game — requires uninterrupted time in a safe, supportive space.

“Connected Learning” suggests that we value informal, out-of-school learning and link it with formal learning in a more coordinated way. Looking into communities as places for learning can reveal troubling disparities in learners’ access to safe and supportive “third spaces”, alternatives to the home and school environments.

Students whose local environments offer little in the way of supportive third spaces — physical or virtual — have limited opportunities for tinkering and play. Advocates of connected learning, then, should not focus only on designing learning environments in school, but also must focus on community-building more broadly.

Public libraries, religious groups, after-school clubs, and makerspaces all can offer much-needed proximal, open-door access to information, social opportunities, mentors, and tools for production and sharing. In a response to this need, many cities have recently seen an influx of “makerspaces”, community spaces for arts, technology, and tinkering.

Assemble is one example of a third space that I visited when I lived in Pittsburgh a few years ago. Hosted in the city’s Penn Avenue district, Assemble’s goal is to connect curious learners — young and old — with artists, technologists, and makers. They work toward these goals in hosting free events for young people, including “Girls’ Maker Night”, “Imaginative Engineering”, and “Time Travel Learning Party” (Assembling Connections).

The second necessary resource for tinkering is time. Quest to Learn is an exemplary case of an urban public school that incorporates connected learning into a game-like curriculum. During the Boss Level project-based challenge, the school gives students most of the day to work on group productions at length. However, this open-ended time for tinkering has been chipped away at under parental pressure. The Quest to Learn case study found that less-privileged families in particular pushed the school to limit connected learning experiences like Boss Levels in favor of more traditional pedagogical offerings, “because their childrens’ options in the New York City school system depend largely on test scores.”

Success in creating schools centered around connected, playful learning requires that we work closely with families and communities to show why and how this approach can lead to learner success.

Failing to connect with and gain the support of communities when pushing for educational reform can prevent even a $100 million movement from achieving meaningful change (Assessing The $100 Million Upheaval Of Newark’s Public Schools).

As we explore the topic of social learning in the digital age together,

I would love to learn from your experiences.

Please share your thoughts by commenting below!

Do you agree that connected learning reforms should have an equity agenda?

What other obstacles to networked learning do less privileged learners face?

In what ways do you promote networked learning in your instruction?

Maria,

Once again you have pushed my thinking. If we are to truly educate ALL of our students, then equity certainly needs to part of the conversation. Several years ago, my district was trying to make a decision between going 1:1 with devices or a BYOD plan. We do not have a population that is diverse in race or ethnicity. But we have quite a bit of disparity in socioeconomic status. The decision to go 1:1 was in large part to try to level the playing field. In year two of our initiative, students were permitted to take these devices home if they paid a $60 insurance fee. Does this begin to address the equality issue? Possibly. I think the bigger shift could be the transformation of our instructors from experts into learners and mentors. This may be much more difficult to accomplish and will require re-education as well as lots of support.

Heidi – your school’s move to a 1:1 device program sounds like a great first step to leveling the playing field in your community. As Sean mentioned, the insurance fee could still be a hardship for some families, and access to high-speed internet and a safe space to use the devices are additional hurdles. The question of equity in education is such a big one that designing learning environments can only be a small piece of the puzzle. That said, connected learnings’ emphasis on valuing all student voices definitely seems to be a step in the right direction.

Hey Maria,

I continue to enjoy your writing. You have a great voice, a clarity of thought and your compassion as an educator comes through.

The “Networked Learning Paradigm” diagram is well selected. I found it illustrated the concepts you discussed and illustrated my thoughts well. I plan to use it in training sessions with my teachers. In particular, as I view the image, I like that it illustrates both that the teacher is at the center of the learning process and that the student is at the center of their learning.

Sadly the problems of inequity you raise have been going on forever and…all indicators are that this problem will continue. Social class structures, as you point out, are indeed the primary indicators of success. Check out the summary of one study looking at this in an unusual way. How many words are spoken to children based on economic status.

http://literacy.rice.edu/thirty-million-word-gap

To your question, “Do you agree that connected learning reforms should have an equity agenda?” I gotta be honest, I struggle with questions like this because, as I see it, the only real answer is, “Yes.” Any answer to the negative would be a horrible answer yet the problem persists.

What you ask is important. My answer would be that “connected learning reforms” is but one part of equity agenda reform that is needed.

To your other question “What other obstacles to networked learning do less privileged learners face?” I refer to the link I shared above. The number of obstacles less privileged learners have to overcome are numerous. Heidi’s comments about the cost of laptops is another example. I’m sure that the $60 insurance fee some of the families would have to pay would be a challenge for welfare families.

Sean

Sean – thanks for linking to the word gap study. That really highlighted for me the effect that differences in the home environment can have on in-school formal learning. I think one advantage of connected learning is its emphasis on linking learners to voices, opinions, texts, and materials outside of their local community. If students are in a community context with relatively low literacy levels, exposure to and engagement with people of different classes, generations, and ability levels could be enriching.

I’m really curious about your experience in Hong Kong with respect to educational reform with an equity agenda. Is this kind of conversation taking place in your community? A long history of questioning equality in that region…

Hi Maria,

I really appreciate you bringing up the economic issues that prevent much of what we try to do with technology from working. I work for a public school district, and this is one of the topics I struggle to explain to others. Once a student sets foot on campus, they have access to good equipment, a fast network, useful software, and guidance on how to use it all efficiently. Based on survey results from the last few years, most students have this access at home. There are still fair amounts who do not. If we want everyone to be a part of the learning community, the means to be a part of that community need to be available at home.

You mention open door access to information in Pittsburgh. I think that is a great opportunity for anyone who is able to attend. The problem I face in my community with something like this is transportation. Although the schools and libraries are open and available to students, very often they cannot get there. In a rural town, public transportation is not available. Just another example of economic status preventing equal learning…

Ben – thanks for reading and commenting. Your point about transportation is an important one that reinforces the idea of in-school formal learning as only one part of a much larger community system. The NPR story I linked to also talked about transportation as one element that can have meaningful effects on learners’ well-being and ability to learn well:

“Newark, throughout all time, had been a city where kids walked to school. There were many small neighborhood schools, and there was no bus system that took kids to school, except in the case of kids with special needs who had to go to special schools.”

Then, when Newark implemented educational reform that required families to choose schools through an online algorithmic sorting system:

“And it turned into a massive upheaval in just the way school was experienced by children and families in Newark. And it was done, again, without a process of vetting with the community to see, well, how if, you know – will this new system work for these children and families? When a school is closed, children had to walk through very dangerous territory, you know, sometimes through gang territory, through drug dealing neighborhoods. And none of that was kind of vetted in advance to see what can we do for these kids to make sure they’re safe?”

Your comment reminds me that designing learning environments – networked/connectivist or otherwise – requires thinking about how that environment will fit into a broader cultural context.

Maria, as your peers have commented, you raise some very good points about equity and design. I won’t reiterate the discussion points, but I will add to one aspect that you mentioned: i.e., even students who have regular and sustained access to technology and online resources may not know how to leverage these resources for learning. This is what the national ECAR study finds consistently when looking at undergraduates’ use of technology: http://www.educause.edu/library/resources/ecar-study-undergraduate-students-and-information-technology-2013. So there is definitely a role for experts and teachers/mentors to play in shaping learning with technology.

I really like and appreciate this comment you made, “Advocates of connected learning, then, should not focus only on designing learning environments in school, but also must focus on community-building more broadly.” Building the community more broadly would certainly aid in the connected learning process. I believe an example from a previous week mentioned the idea of parks and science centers and connecting them in ways.