To learning much inclined,

Who went to see the Elephant

(Though all of them were blind),

That each by observation

Might satisfy his mind…”(Saxe, J. G., 1873)

The Tale of the Elephant

Designing an effective learning experience – with mobile technologies or otherwise – requires a systematic, holistic, and human-centered approach. It can be tempting to default to a reductionist mindset, one that holds a singular focus on the digital affordances of a mobile tool or technology. Pea and Maldonado’s eight-part framework of device features is one fitting example of the techno-centrism common in much of the early research in mobile learning (Pea & Maldonado, 2006, p. 428) (Kukulska-Hulme et al., 2009, p. 7).

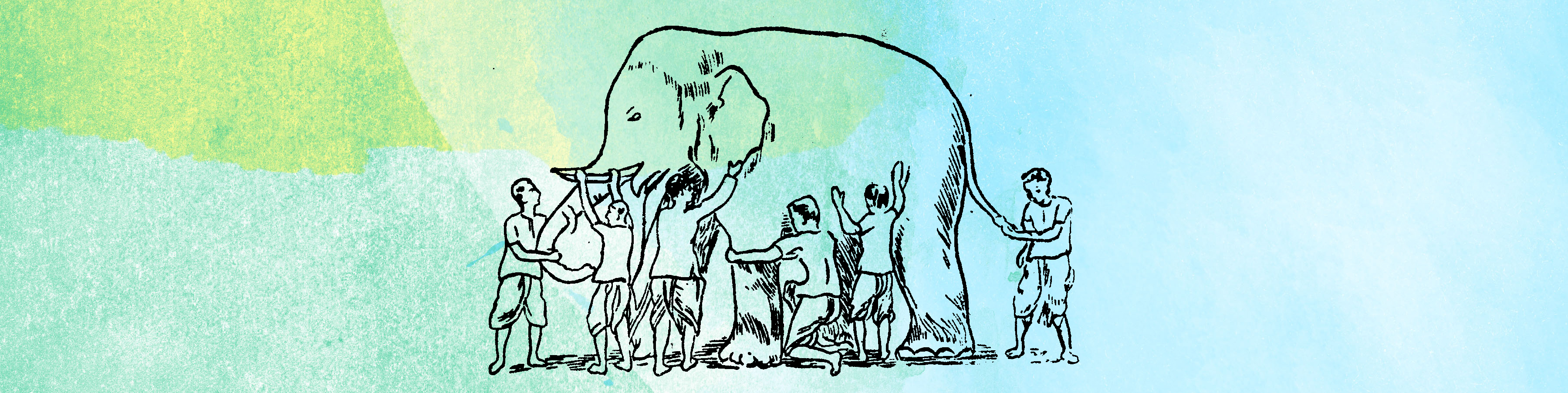

To illustrate the inadequacy of this limited approach, we can look to the tale of the blind men and the elephant. Touching only a small section of the animal’s body, each man was restricted in his perspective and ignorant of the broader, essential whole of the creature. (“It’s a rope! No, it’s a column!”)

When a learning intervention fails to consider what Nelson and Stolterman in The Design Way call the “essential relationships and critical connections” of the larger system in which it is embedded, it will likely prove ineffective and unsustainable (Nelson & Stolterman, 2012, p. 57).

One example of the human effects of such a disconnect can be found in Julian Orr’s ethnography of repair technicians working at Xerox. The company’s training and development initiatives were based on an idealized, simplistic model at odds with the actual practices of the technicians. When the workers resisted compliance with these materials, Xerox labeled the high-performing technicians as “untrainable, uncooperative, and unskilled.” In turn, the experience convinced the workers that the company misunderstood and undervalued their considerable skills (Brown & Duguid, 1991, p. 43).

We must ask ourselves: how many learners have been similarly failed by interventions that succeed in delivering educational content but otherwise poorly account for and respond to their very real human needs, experiences, and practices?

Arriving at a Systematic, Human-Centered Approach

A series of early mobile learning projects implemented this technology-driven approach, developing and testing educational software, hardware, graphical user interfaces, and so on (see the HandLeR and Leonardo da Vinci Programme projects, for example) (Kukulska-Hulme et al., 2009, p. 2-7). In the decades following these foundational efforts, the mobile learning design community has come to look beyond the technology to embrace socio-cultural practices and contextual constraints as central, critical factors influencing the success of a learning intervention.

In an educational system, seemingly discrete elements (human, technological, logistical, social, cultural, economic) interact in unexpected ways. Only by looking at the design problem from multiple perspectives can we gain a better sense of the system as an emergent whole. Research that shatters the framework of “normative users” and “normative behaviors” to reveal how real people use technologies in their everyday lives gives us critical information with which we can ground our design decisions. Yardi and Bruckman’s exploration of socioeconomic differences in family technology use and McKay et al.’s look at the emergent communication practices of Western youth are two examples of powerful sociocultural research (McKay, Thurlow, Zimmerman, 2005) (Yardi & Bruckman, 2012).

A systematic, human-centered strategy aligns with the model of design as a service relationship proposed in The Design Way. In this model, “design ideally is about service on behalf of the other – not merely about changing someone’s behavior for their own good . . .” (Nelson & Stolterman, 2012, p. 41). We find further support for this point from Pachler who argues that we can only achieve success in using mobile technologies for learning when recognize what learners really do and impose “the personal on the technical” (Pachler, 2010, p. 84).

Only with a systematic approach can the learning designer hope to resolve the tensions between “scale, sustainability, and appropriateness” that characterize the challenge of using mobiles to support learning in meaningful and effective ways (Traxler, 2013, p. 139).

Sources

Brown, J. S., & Duguid, P. (1991). Organizational Learning and Communities-of-Practice: Toward a Unified View of Working, Learning, and Innovation. Organization Science, 2(1), 40-57. doi:10.1287/orsc.2.1.40

Kukulska-Hulme, A., Sharples, M., Milrad, M., Arnedillo-Sanchez, I., & Vavoula, G. (2009). Innovation in mobile learning. International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning, 1(1), 13-35. doi:10.4018/jmbl.2009010102

McKay, S., Thurlow, C., & Zimmerman, H. T. (2005). Wired whizzes or techno-slaves?: Young people and their emergent communication technologies. In Williams, A., & Thurlow, C. (Ed.), Talking adolescence: Perspectives on communication in the teenage years. (pp. 185-203) New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

Nelson, H. G., & Stolterman, E. (2012). The design way: Intentional change in an unpredictable world. Cambridge, Massachusestts: The MIT Press.

Pachler, N., Bachmair, B., & Cook, J. (2009). Mobile Devices as resources for learning: Adoption trends, characteristics, constraints and challenges. Mobile Learning, 73-93. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0585-7_3

Pea, R. D., & Maldonado, H. (2006). WILD for learning: Interacting through new computing devices anytime, anywhere. In K. Sawyer (Ed.), Cambridge university handbook of the learning sciences (Chapter 25). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Saxe, J. G. (1873). The blind men and the elephant. In The Poems of John Godfrey Saxe. Boston: James R. Osgood and Company.

Traxler, J. M. (2012). Mobile learning across developing and developed worlds: Tackling distance, digital divides, disadvantage, disenfranchisement. In Handbook of mobile learning (pp. 129-141). New York, NY: Routledge.

Yardi, S., & Bruckman, A. (2012). Income, race, and class: Exploring socioeconomic differences in family technology use. Proceedings of the 2012 ACM Annual Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 3041-3050. doi:10.1145/2207676.2208716

Maria – I really appreciated that you presented the fable about the blind men and the elephant as an analogy for the different ways that people use and interpret content delivered via technological means. It really fits!

Your perspective as a designer comes through and is certainly a critical aspect that needs careful thought when designing an app or e-learning module. However, because there is such a difference between how different genders (the studies focused on male v. female, but I wonder about those with different views about their gender) and different socioeconomic groups use technology, is it possible to create a design that can adapt as the software learns users’ preferences? This might bleed into the ‘personalized learning’ that the Zuckerburg Foundation is now focused upon.

For me, there is value in current technology-enhanced learning, but I wonder what the future might hold. Here’s a great link from New Zealand that I found interesting: http://www.education.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Ministry/Initiatives/Lifelonglearners.pdf Do you think the framework presented here would provide the diversity that is needed?

–Pat

Maria,

Like Pat, I enjoyed your analogy to the elephant story. Each man was only focused on their own task without taking into account the information the other men needed.

This was the case in some early mobile-learning projects that crossed the divide between technology and pedagogy. Kukulska-Hulme points out that the mere fact that the technology is mobile creates new learning opportunities. “It also challenges views of formal education as the transmission or construction of knowledge … calling instead for the exploitation of technology in bridging the gap between formal and experiential learning.”

That is, when technology is mobile, the learner has the ability to interact with the world around him or her while utilizing the device.