My name is Maria and I am a coder, cellist, and tech-minded teacher working in online higher education. For the past 8 years, I have taught a large online Gen Ed performing arts course for Penn State University Park. This has been a rewarding first-hand experience of the challenges and promises of tech-assisted teaching and learning. My struggle has been to push for speed and scale while ensuring that my students have high-quality and hopefully transformational learning experiences.

My class has a largely browser-based delivery hosted on the ANGEL (and now Canvas) LMS and the Sites@PSU platform. While my students may be accessing course content through their phones and tablets, I have little solid insight into their practices in that regard. This summer, I hope to learn about the educational domains best-served by a mobile-driven approach and the technologies and practices that can support meaningful learning outcomes.

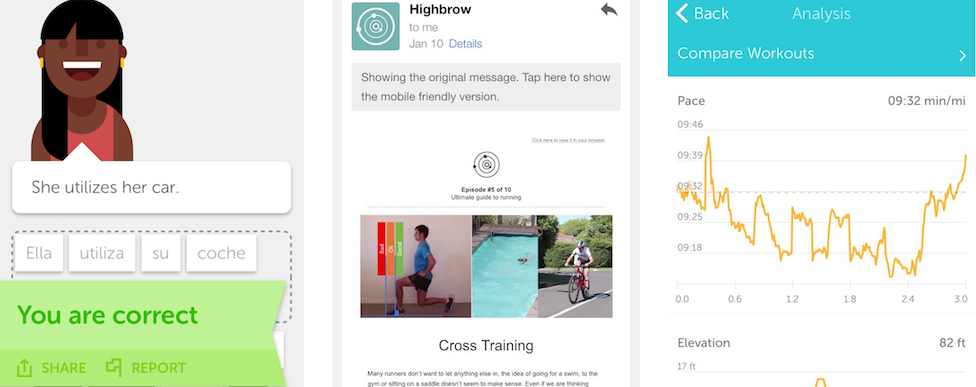

In my personal life, I use apps and mobile services daily to support my informal, interest-driven learning. My conjugation skills have grown rusty since my days as an undergrad French major, so I use Duolingo — a slick language learning app that combines bite-sized drills and gamification elements like badges, leaderboards, and in-app rewards to motivate users. I also subscribe to Highbrow, an email-based service that sends free 5-minute lessons on a topic of my choosing to my inbox every morning. While less overtly designed as an educational app, Runkeeper gives me quantified analytics about my running practice, insights that drive behavior change.

While I use bite-sized learning modules myself, after 8 years of working in online education, I harbor some skepticism. While Highbrow, for example, lets me get a taste of knowledge on the go, it is at its core little more than the kind of one-way information push so prevalent in stale online teaching — just in a smaller, more mobile package.

Duolingo, Highbrow, Runkeeper

I find that real innovation comes when we tap into the unique capabilities of mobile devices – features including bioanalysis, location awareness, and natural language processing. The 2014 NMC Horizon report for Higher Education supports this point, arguing that quantified self technologies and virtual assistants will find adoption in the next four to five years. Location-awareness services see a more immediate use, with the 2015 NMC Horizon report for Museums arguing their time-to-adoption horizon to be in the next two to three years.

The framework that guides and grounds my analysis of mobile learning technologies is David Jonassen’s model of “Mindtools”. Pushing back against learning “limited to the acquisition and repetition of information,” Jonassen argues that digital tools should be used instead as supports to learn not only from, but with (Jonassen, Carr, & Yueh, 1998, p. 1).

Below, I explore the promises and practices of the mobile technologies covered in the Horizon reports, with an eye towards how we might use them as Mindtools to support critical thinking and meaning making.

Location Based Services

Location-based services leverage mobile technologies’ GPS, RFID, and Bluetooth capabilities to offer ‘just-in-time”, or rather, “just-in-place”, information. Most of us bring our smartphone with us wherever we go. Museums have responded to this trend by developing personalized navigation, content, and recommendations to be pushed through their patrons’ devices. These kinds of targeted, tailored mobile guides can enhance visitors’ learning by allowing for a more embodied, in-situ experience of instructional content. MIT’s “Local Warming” exhibit, which uses WIFI-based motion tracking to trigger localized IR lamps, is an especially interesting case of an embodied learning experience. The challenge for museums using location-based services is to ensure that they are using mobiles not only to transmit information, but to respond and adapt to their patrons’ interests, motivations, and needs.

Quantified Self

Many modern smartphones come equipped with advanced sensors like accelerometers, motion detectors, and heart-rate monitors. This sensory information can be captured and stored in databases that offer users data about their personal health and habits. Mobile apps offer intuitive, easy-to-read graphical user interfaces that help us to understand and explore this data, ideally leading to insights that can spark behavioral change. The trend of capturing, storing, and analyzing personal metrics is known as the “quantified self movement”.

Jonassen identifies several classes of Mindtools: semantic organization tools, dynamic modeling tools, information interpretation tools, knowledge construction tools, and conversation and collaboration tools (Jonassen et al., p.1). Quantified self applications might be best described as information interpretation tools as they offer visualizations that help learners to understand otherwise complex and abstract data.

By experiencing personal data visually, we can more easily draw interpretations and extract insights. Data analysis is an increasingly important skill for learners drowning in data in the “information age”. Supporting students in analyzing data at the personal level might lead to a transfer of that skill to more external, abstract datasets.

Virtual Assistants

Advances in machine learning and natural language processing have enabled the development of virtual assistants, technologies that can truly act as partners in our learning experiences. When restrictions on users’ mobility (i.e. information input only through typing) and expression (i.e. information input only in a specific syntax) are lifted, we can interact with our devices as if they were humans. We can ask our devices questions, converse with them about ideas and information, and outsource our rote tasks to them. These devices offer a navigational flexibility that truly puts the user in control. Conversational user interfaces can be used to push learners’ critical thinking through a sort of virtual Socratic dialogue. As we saw with Jill Watson, an AI teaching assistant, virtual assistants can respond to basic learner questions, freeing up the human instructor to engage in more subjective, higher-order pedagogy.

As these now far-horizon mobile technologies begin to enter the cutting-edge of teaching and learning, we will see if they continue to serve as basic information delivery systems, or if they approach a more transformative use as intellectual partners we can learn with as we engage in meaning making and critical thinking. I’m eager to find out more about mobiles as Mindtools moving forward.

Sources:

Jonassen, D. H., Carr, C., & Yueh, H. (1998). Computers as mindtools for engaging learners in critical thinking. TechTrends, 43(2), 24-32. doi:10.1007/bf02818172

NMC Horizon Report: 2015 Museum Edition (Rep.) Retrieved http://cdn.nmc.org/media/2015-nmc-horizon-report-museum-EN.pdf

NMC Horizon Report: 2014 Higher Ed Edition (Rep.) Retrieved http://cdn.nmc.org/media/2014-nmc-horizon-report-he-EN-SC.pdf

As we explore the topic of teaching and learning with mobile technologies together, I would love to learn from your experiences.

Please share your thoughts by commenting below!

What apps or mobile services do you use in your daily life?

What are your experiences with conversational interfaces like Siri or Cortana?

Hi Maria, thank you for your insightful first posting! Doubtless you will have a different perspective with regards to this online course as you have been on “the other side” (Adele, anyone?) as an instructor for many years!

I agree that there is an important distinction between simply learning “from” mobile tools and learning “with” mobile tools (as Jonassen argues).As we shift into looking more deeply at the literature surrounding how people’s learning experiences can be facilitated by mobile technologies, I’ll be curious to see if your thoughts regarding the term “m-learning” grow and change.

More to come,

Lucy

Hello from the other siiide! Thanks for your comment, Lucy. I’m very much looking forward to diving into the literature and learning from your and others’ expertise in this field.

Hello, Maria!

First, thank you for swinging by to comment on my blog! I am a newbie to Sites, and your skills here are fantastic!

I look forward to working with you in this course as well as in Design Studio.

Thanks for visiting and for the kind words, Dawn! I probably spend too much time playing with the visual elements, but I find it to be really fun.

Hey, Maria!

A coder! Awesome! I’ll admit I really want to learn to code but am so intimated. I’ve attended several Code.org workshops to learn how to bring thinking skills used in coding my school district– but truthfully, I need more hand holding than the kids do.

You have a unique background and set of life experiences that I think will add dimension to our course conversations!

Looking forward to learning wth you!

Pam

Thanks for your comment, Pam! Skillcrush is one of my favorite resources for learning about coding. They present the material in a really fun, accessible voice that brings down the intimidation factor. I recommend signing up for their newsletter – it’s full of great info and resources: http://skillcrush.com/