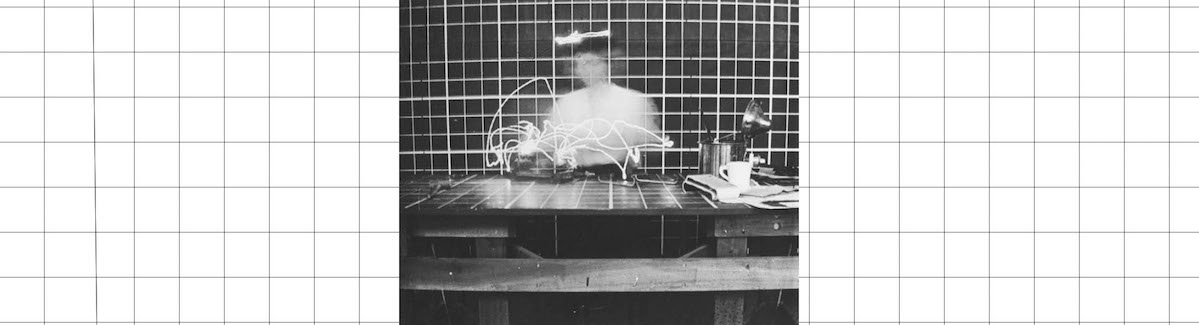

Motion efficiency study by Frank Gilbreth, c. 1914. Collection: National Museum of American History

The Shift to Syncretism

The industrial spirit of the 20th century prized efficiency, predictability, and optimization above all. In this cultural landscape, the scientific method came to dominate as the hallmark method of inquiry across disciplines. The post-World War II corporate world, for example, saw the rise of Taylorism and management science as popular applications of the scientific method for leaders in search of universally true, optimized business solutions (Taylor, 1967). We only need to look to the Gilbreth motion studies in industry for evidence of this rationalist approach to understanding and regulating human thought and behavior.

Learning scientists targeted education in much the same way, with controlled empirical studies of cognition dominating the research landscape. Design guru Donald Norman characterized this kind of analysis, which sought to understand the “pure intellect”, as fundamentally isolated – from the world, from other forms of knowledge, from the broader abilities of the learner as a whole person (Rogers, 2011, p. 59 ).

The appeal of the scientific tradition is obvious; it promises some guarantee of certainty and predictability of outcomes. In this promise, though, lies its essential and damning misalignment with a powerful force of unpredictability: humanity. In a world ruled by messy, networked human behavior, complexity can be the only guarantee. The Design Way reminds us that in the artificial, designed world of the real, efforts to discover universal truths like those that exist in the natural world are futile at best (Stolterman & Nelson, 2013, p. 28).

Given this one guarantee, real-word challenges require not only a rational, reductionist mindset, but an integrated approach that accounts for and honors the “challenge and mystery” of complex, emergent systems and their component elements. Stolterman and Nelson call for a sort of syncretism, a compound form of inquiry that integrates the divergent epistemologies of the true, the ideal, and the real (Stolterman & Nelson, 2013, p. 29-34).

We can find evidence of this language of unity in the learning sciences, too. During the past 30 years, learning research has moved away from largely lab-based studies towards situated, classroom-based research and ethnographic studies “in the wild”. In 2006, members of LIFE, a multi-institution NSF Science of Learning Center, called for the 2010s to be “a decade of synergy” among the different traditions of learning theory (Bransford et al., 2006, p. 209-10). The Design Way asks the designer to choose from and apply the relevant methods of three traditions of inquiry. Likewise, Bransford et al. envision a kind of blended inquiry in which the research strands that study implicit learning, informal learning, and formal learning share methods, research tools, and insights as needed.

Switching between, synthesizing, and selectively applying elements of distinct traditions of inquiry requires an adaptive neural flexibility. Maintaining a “softness” of mind helps us to hold and examine seemingly competing or contradictory ideas in the same mental space. This flexibility, however, may not come naturally for most. Indeed, facing a challenge to one’s deep-rooted mental models and core competencies can be a deeply emotional and uncomfortable experience (Bransford et al., 223). With training, though, we can arrive at a degree of comfort born of familiarity with the ambiguity and disconfirmation so intrinsic to the iterative design process (Bransford et al., p. 226).

Building on what Stolterman and Nelson call the foundations of the design way (The Ultimate Particular, Service, Systemics, The Whole), I propose a three-part training plan for the aspiring designer that primes the mind for both reflective inquiry and action: active listening, mindfulness, and visualization.

Active Listening

Active listening supports the other-serving relationship that Stolterman and Nelson argue is a central characteristic of the design way. The practice of active listening involves making a focused effort to fully hear and understand another’s communication. For the designer operating in a service relationship, active listening allows the client’s vision to find shape and expression. In listening actively, the designer places aside – temporarily, at least – his or her established schema of what is correct or desirable. The challenge is to understand, not to be understood.

To train the skill of active listening in support of reflective inquiry, the learning designer in communication with a client – a Subject Matter Expert, for instance – should practice:

- Giving the client full attention of sight, sound, and mind.

- Gently setting aside distracting or competing thoughts that develop while listening.

- Offering affirmative verbal and nonverbal feedback to the speaker.

Mindfulness

Reflective inquiry centered on hearing the client’s needs or desires is only the first part of the service relationship, though. The practice of mindfulness allows another more subtle and inchoate expression to take form. The Design Way tells us that a design process achieves success when the design “transcends the original stated expression, resulting in the ‘expected unexpected’” (Stolterman & Nelson, 2013, p. 42).

Understanding the full message means that we are keyed into not only the ideas expressed verbally, but also the contextual and nonverbal communication. Being mindful, maintaining a state of active, open attention to the present moment, allows the designer to pick up on the “gossamer” threads of the client’s desiderata, of which he or she may not yet be conscious (Stolterman & Nelson, 2013, p. 43).

Here, the qualities of intuitive inquiry come into play. Building on ambient sense data, the designer can patiently, but proactively tease out a clearer expression of the client’s unstated or unknown desires. In the case of the learning designer, a SME may unconsciously shift in her chair and cross her arms in reaction to a prototype perceived to be displeasing. Or, she leans forward and raises the volume of her voice in reaction to a suggestion well aligned with her desiderata. A self-serving or self-focused designer does not have the alert mental presence required to pick up on these subtle cues.

To train the skill of mindfulness in support of intuitive inquiry, the learning designer should practice:

- Asking the client for clarification of his or her ideas.

- Restating or summarizing the client’s comments for confirmation.

- Identifying and gently pushing the line of thinking about nascent ideas.

- Maintaining a clear focus on the present moment.

- Paying close attention to the client’s nonverbal cues.

Visualization

With practice in active listening and mindfulness, the designer supports the service relationship by building an understanding of the client’s needs and desires. From there, the designer is tasked with understanding how that vision fits within a broader, complex system. By taking a holistic approach, the designer considers the full range of component elements that make up a system as well as the properties that emerge from the interactions of those elements.

The Design Way argues that understanding a system as a combination of discrete constituent elements is inadequate. So too, then, is an approach that considers the whole of a system from only one perspective. To fully “see” a system, the designer needs to mentally move around and through it by way of shifting “station points” (Stolterman & Nelson, 2013, p. 68).

Training in the practice of visualization may prove useful for a designer working to move between and integrate multiple perspectives. The designer should practice:

- Resting the body and closing the eyes.

- Visualizing the system at play in the design challenge as a physical space.

- Visualizing the self moving through and exploring that physical space.

- Making note of the people, spaces, and objects that occupy the space.

- Making note of any underlying emotion or mood in the space.

The Learning Designer’s Toolkit

Training in the practices of active listening, mindfulness, and visualization can help the designer to harness the compound form of inquiry unique to the design tradition. Active listening supports the foundation of the service relationship by helping the designer to grasp the client’s stated desires and needs. Mindfulness incorporates an element of intuition, or “unconscious knowing”, that allows for an understanding of unspoken or ambient communication by the client. Together, active listening and mindfulness help the designer to create an “ultimate particular” that transcends the client’s original expectations. Finally, the practice of visualization helps the designer to develop the mental flexibility needed to understand complex, emergent systems from multiple perspectives. I propose this three-part training as an addition to the frameworks and models that Stolterman and Nelson offer, all valuable tools for those aspiring to embody “the design way”.

Sources

Bransford, J., Stevens, R., Schwartz, D., Meltzoff, A., Pea, R., Roschelle, J., . . . Sabelli, N. (2006). Learning Theories and Education: Toward a Decade of Synergy. Handbook of Educational Psychology, 209-244. doi:10.4324/9780203874790.ch10

Nelson, Harold G., and Erik Stolterman. The design way: Intentional change in an unpredictable world. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT, 2013. Print.

Rogers, Y. (2011). Interaction design gone wild. Interactions, 18(4), 58-62. doi:10.1145/1978822.1978834

Taylor, F. W. (1967). The principles of scientific management. New York: Norton.